Site Planning: An Essential Guide for Architecture Students

P.S: Article updated on 29th March 2025

Site planning is one of the most crucial—yet often underestimated—aspects of architectural design. Before a single brick is laid or a line is drawn on a blueprint, the site must be understood, respected, and shaped. For architecture students, learning how to analyse and plan a site is fundamental. It bridges the gap between theoretical design and practical implementation, grounding creative vision in the real-world complexities of land, nature, and human use.

What is Site Planning?

At its core, site planning is the process of arranging buildings and structures on a piece of land, along with shaping the open spaces between them. It is an art as much as it is a science, blending architectural creativity with urban planning logic. A site plan doesn’t just tell you where things go—it tells a story of space, movement, interaction, and context.

Whether the site involves a single house, a group of buildings, or an entire neighbourhood, a well-thought-out site plan ensures the environment enhances, rather than limits, the design. Good site planning considers environmental, cultural, and infrastructural factors to produce a plan that is contextually appropriate, functional, and aesthetically pleasing.

The Importance of Site Planning in Architecture

For architecture students, understanding site planning is not just a box to tick. It is a foundational skill that will influence every project they work on. It affects:

- Building orientation and solar access

- Integration with the natural landscape

- Accessibility and movement

- Energy efficiency and sustainability

- Quality of life for occupants and users

Ignoring site factors can lead to designs that are uncomfortable, inefficient, or even unbuildable. Conversely, designs that grow organically from the site often feel more harmonious and enduring.

The Environmental Dimension: Designing with Nature

A sensitive and responsive design starts with understanding the site’s environment. This doesn’t just mean weather or trees—it’s about decoding the site’s past, present, and potential.

Key Environmental Factors

Geology

Beneath the surface lies the hidden strength of the site. Knowing the type of bedrock and its stability is crucial for deciding foundation types. Rocky outcrops, fault lines, or soil depth all impact construction decisions. Geological formations may also influence the availability of groundwater, mineral deposits, and natural thermal properties.

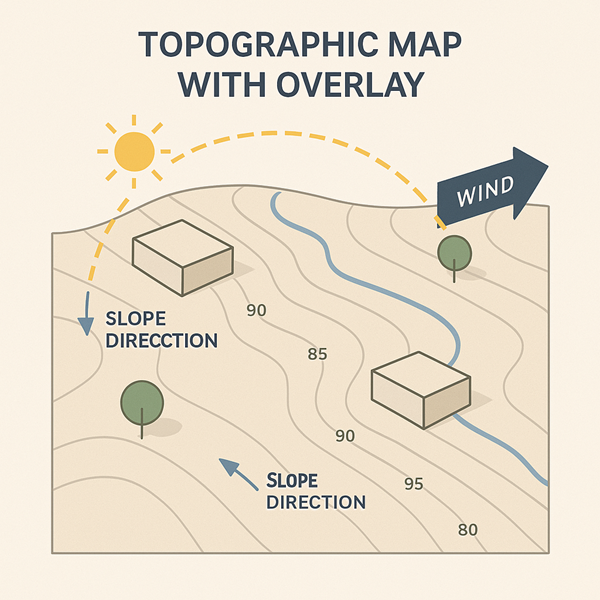

Topography

The contours of the land dictate how a building will sit and interact with its surroundings. Slopes, ridges, and valleys influence drainage, accessibility, and views. A good architect learns to work with the land—not against it. A topographic survey reveals:

- Drainage patterns

- Natural erosion paths

- Areas with scenic views

- Suitable spots for construction

Hydrography

Where does water flow? Are there streams, ponds, or marshes? Is the water table high? Site planning must respect water movement to avoid future flooding or erosion. Hydrography also reveals opportunities for integrating water features as part of sustainable design strategies.

Soil Conditions

Soil isn’t just dirt—it’s a complex system that supports buildings and plant life. Analysing soil type helps determine bearing capacity, drainage potential, and suitability for landscaping. The following aspects must be studied:

- Load-bearing capacity

- Permeability and drainage

- Erosion potential

- Fertility for vegetation

Vegetation and Wildlife

Mature trees, native shrubs, and wildlife habitats all contribute to the ecological and visual character of the site. Preserving these features can enhance sustainability and user experience. Vegetation analysis aids in:

- Identifying species to preserve

- Planning shaded outdoor areas

- Designing windbreaks

- Supporting biodiversity

Climate and Microclimate

Orientation to the sun, wind patterns, humidity, and precipitation all shape how buildings should be placed. Passive solar design, ventilation strategies, and thermal comfort all begin with climate analysis. Microclimatic conditions vary across a site and must be carefully studied.

Site Analysis: A Layered Approach

Understanding a site requires a multi-layered approach:

Above the Ground

- Sun path and solar access

- Air circulation and ventilation

- Views and visual connections

- Height restrictions

On the Ground

- Ground cover and vegetation

- Circulation paths

- Surface water drainage

- Existing structures

Below the Ground

- Soil layers and types

- Rock formations

- Underground utilities

- Archaeological remains

Each layer reveals clues about the site’s potential and constraints. Students are encouraged to visit the site at different times of day and in different weather conditions to observe how it behaves.

Human and Cultural Factors: Designing with Context

Architecture doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It must respond to its cultural and urban context. Site planning must account for how people interact with the site and how it fits into the larger urban or rural fabric.

Key Cultural and Infrastructural Considerations

Land Use and Ownership

Know what the site is currently used for and who owns it. Surrounding land uses (residential, industrial, recreational) can influence design choices, privacy, and noise levels. Adjacent land ownership can also affect:

- Potential expansions

- Shared access roads

- Privacy requirements

Linkages and Circulation

Analyse both vehicular and pedestrian traffic patterns. Are there existing roads, bus stops, or cycle lanes? A site should connect, not isolate. Planners must account for:

- Entry and exit points

- Service access

- Parking areas

- Accessibility for all users

Utilities and Infrastructure

Ensure access to water, electricity, sanitation, and stormwater drainage. Without these, even the best design cannot function. Infrastructure planning involves:

- Utility line placement

- Stormwater management

- Fire safety and emergency services

Density and Floor Area Ratio (FAR)

These zoning parameters control how much can be built. Understanding them helps you work within legal limits while maximising design quality. Site coverage and building height regulations are also relevant.

Existing Buildings and Heritage

Retaining or responding to historical structures can add character and meaning. Respecting architectural heritage ensures designs are rooted in place. In conservation areas or near listed buildings, planning restrictions must be observed.

Off-Site Nuisances and Safety Hazards

Be aware of noise, pollution, or visual intrusions such as highways or power lines. Also note any safety risks like steep cliffs or unstable slopes. Safety features should be incorporated into the design:

- Guard rails

- Lighting

- Buffer zones

The Design Process: From Analysis to Concept

Once a thorough site analysis is completed, students can begin conceptualising their designs. A good site plan emerges from:

- Synthesising information

- Prioritising functions

- Exploring alternatives

- Testing scenarios through diagrams

Steps in Site Planning Design:

- Site Inventory – Gather all relevant data.

- Site Analysis – Identify constraints and opportunities.

- Concept Development – Create bubble diagrams and zoning plans.

- Circulation Planning – Define movement patterns.

- Spatial Organisation – Allocate spaces according to use and hierarchy.

- Landscape Integration – Add green spaces and outdoor features.

- Detailed Planning – Prepare final drawings with scale and annotations.

Landscape Design and Outdoor Spaces: Completing the Picture

Site planning doesn’t stop at building placement. The spaces between buildings matter just as much. Thoughtful landscape design enhances usability, beauty, and environmental performance. Key landscape elements include:

- Pathways and plazas

- Seating areas

- Playgrounds and gathering spaces

- Green buffers and screening

- Rain gardens and bioswales

Sustainable landscape planning also contributes to reducing the heat island effect, improving stormwater absorption, and promoting biodiversity.

Architecture students must also be aware of planning policies and legal frameworks that influence site planning. These include:

- Local development plans

- Building regulations

- Environmental impact assessments (EIA)

- Accessibility standards (e.g., inclusive design)

- Conservation and heritage policies

Understanding these ensures that designs are not only creative but also feasible and compliant.

Tools and Techniques for Site Planning

Modern site planning is aided by several tools and methods:

- Surveying instruments: Total stations, GPS devices for accurate site measurements

- GIS (Geographic Information Systems): For mapping terrain and analysing spatial data

- CAD and BIM software: For drafting detailed site plans

- Model making: Both physical and digital models for testing massing and layout

- Environmental simulation tools: To study sun paths, wind flow, and shadows

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Site Planning

- Ignoring topography: Designing flat buildings on sloped land can lead to costly modifications.

- Lack of drainage planning: Poor stormwater management can flood buildings.

- Overlooking pedestrian movement: Designs should encourage safe and efficient walkability.

- Neglecting cultural context: A design that doesn’t fit its surroundings may face public opposition or planning rejection.

- Inadequate tree protection: Removing mature trees can increase environmental impact and reduce site appeal.

Why Site Planning Matters?

For architecture students, learning site planning builds critical thinking. It forces you to analyse, observe, and synthesise information before jumping into design. It’s about developing a holistic mindset where the land becomes a collaborator in your creative process—not just a backdrop.

A well-planned site reflects harmony between human needs and the natural world. It ensures longevity, resilience, and joy in the spaces we create. It’s also a critical part of sustainable design, ensuring resources are used wisely and responsibly.

Final Thoughts

As you progress through architecture school, never underestimate the power of good site planning. The most iconic buildings in the world owe their success not only to bold design but also to sensitive integration with their sites.

So next time you get a new project brief, start by walking the land. Sketch the contours, feel the sun, listen to the wind—and let the site speak to you. Because every great building starts with a great understanding of place.

Want to go further?

Create a site analysis board for your next project. Include:

- A topographic map

- Sun path diagram

- Soil profile

- Wind rose

- Circulation maps

- Photos and sketches

This will not only strengthen your design but also impress your tutors and future clients.

I reckon this is the best site to know a wide variety subject on Architecture

Wonderful info..!! presented in d best way with gud examples too…

very informative and covers a wide range of topics pertaining to architecture……

I hope you never stop! This is one of the best site to know a wide variety subject on Architecture. You’ve got some mad skill here, man. I just hope that you don’t lose your style because you’re definitely one of the coolest bloggers out there. Please keep it up because the internet needs someone like you spreading the word.

we wish to convert our existing two story building on a plao of 3000 sft into a old age home,please guide and contact somani 8959595202

Hello Somani,

Kindly email archengdesigners@architectjaved.com for any professional services.

Cheers 🙂

Best site for concise to-the-point information! Thank you so much!

its a best site for my reference for my major project