Forest Landscaping Design: Blending Aesthetics with Sustainable Woodland Management

P.S: Article updated on 29th March 2025

In a world increasingly conscious of environmental sustainability, the role of design within natural landscapes is more crucial than ever. Forest landscaping design — the integration of landscape architecture with forest management — is a growing field that merges ecology, artistry, and human experience.

For both landscape architecture students and forest management professionals, understanding this intersection can offer rewarding career opportunities, ecological benefits, and innovative ways to enrich our connection with the natural world.

This article explores the importance of forest landscaping, techniques used to enhance visual aesthetics, the practical application of silviculture (tree and forest management), and how well-designed woodland spaces contribute to both human wellbeing and environmental resilience.

Why Forest Landscaping Matters

Many people visit forests to escape the bustle of daily life. We hike, camp, cycle, and picnic in woodlands without giving much thought to how the space makes us feel — the shade of the trees, the variety of species, the rustle of leaves, and the surprise of an open clearing all shape our sensory experience.

But walk or drive through a dense, unmanaged forest for several kilometres, and you may find the landscape becomes visually monotonous — a curtain of green with little variation. This sameness can feel calming, but for many, it becomes dull and soporific.

Forest landscaping design seeks to address this by turning forests into dynamic, aesthetically rich environments — without compromising ecological health. By combining the ecological principles of forestry with the artistic sensibilities of landscape architecture, we can transform woodlands into vibrant, functional, and engaging spaces.

The Collaborative Role of Landscape Architects and Foresters

Traditionally, forestry and landscape architecture have operated in different spheres. Foresters focus on timber production, ecological health, and sustainable growth cycles. Landscape architects, on the other hand, prioritise visual harmony, human use, and spatial experience.

But when these two professions collaborate, something magical happens.

-

Foresters bring a deep understanding of ecological succession, species suitability, canopy management, and soil health.

-

Landscape architects contribute visual design strategies, spatial planning, user accessibility, and aesthetic layering.

Together, they can manipulate forest environments to create contrast, rhythm, openness, and intimate enclosures — enhancing both biodiversity and the visual experience.

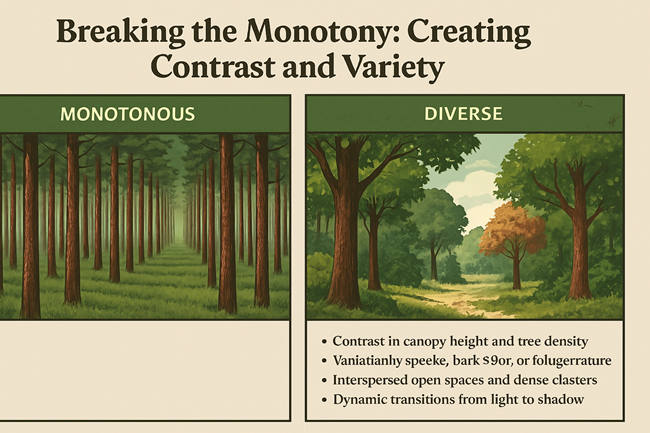

Breaking the Monotony: Creating Contrast and Variety

One of the most common complaints heard from forest visitors is the visual repetition of tree stands, particularly in commercial forests or monocultures. These may be economically efficient, but they often lack visual stimulation.

Imagine driving through 20 miles of the same species of pine planted in rows. It can feel uninspiring and disorienting.

Silvicultural treatments, when carefully applied, can be used not just for forest health or productivity — but to craft visual diversity. Through selective thinning, clearings, replanting, and understory manipulation, forest designers can achieve:

-

Contrast in canopy height and tree density

-

Variation in species, bark colour, and foliage texture

-

Interspersed open spaces and dense clusters

-

Dynamic transitions from light to shadow

Such changes provide rhythm and flow to the landscape, offering different ‘rooms’ and ‘passages’ much like a well-designed garden or building.

Colour and Texture: The Language of Visual Interest

In forest design, colour and texture are key elements. These may seem like purely aesthetic concerns, but they play a crucial role in how people perceive and navigate forest environments.

Colour

The variety of green alone is astounding — from the deep blue-green of spruce to the vibrant chartreuse of young birch leaves. Seasonal changes add drama and beauty: the golden hues of autumn, the deep crimson of Japanese maples, the stark greys and browns of winter bark.

By mixing deciduous and evergreen species, designers can maintain year-round visual interest.

Texture

Leaf shape, bark roughness, branching patterns, and understory planting contribute to a forest’s visual texture. Coarse textures (like large-leafed chestnuts) attract attention and can be used as focal points, while fine textures (like pines or ferns) create soft backgrounds.

Together, colour and texture form a palette for landscape architects to “paint” with, shaping the forest’s atmosphere and emotional tone.

Revealing and Concealing: Managing Views and Vistas

One of the fascinating aspects of forest landscaping is the control of visual permeability — that is, how much of the landscape is revealed or concealed at any given point.

Forests are inherently layered, with opportunities to:

-

Frame distant views of mountains, rivers, or meadows

-

Create winding paths that open into surprise clearings

-

Offer partial glimpses through trunks, building curiosity

-

Use foliage density to block less attractive features (like utility corridors)

Removing certain trees can open panoramic vistas, while selective planting can hide or soften harsh visual elements. The design goal is to create moments of visual excitement and relief — just as in any other form of spatial composition.

Forests as Dynamic and Renewable Landscape Elements

Unlike buildings or terrain, which are relatively fixed, forest vegetation is changeable and renewable. A dense patch of undergrowth today might be an open grove in ten years. This impermanence is a challenge — but also a great opportunity.

Forest vegetation can be:

-

Removed (through felling or thinning)

-

Shaped (by pruning, coppicing, or selecting growth forms)

-

Reintroduced (through selective planting or natural regeneration)

This makes the forest a manipulable design element, responsive to long-term planning and capable of evolution over time. Unlike static landscape features, forests offer a living canvas that adapts with the seasons and the years.

In fact, many forest designs are not just implemented for today’s users but for future generations. Design plans must therefore consider how the forest will grow, change, and regenerate over decades — requiring both vision and patience.

Designing for Multiple Purposes: Ecology, Economy, and Experience

Forest landscaping must be multi-functional. It is not just about beauty but also about:

-

Sustainability: Ensuring biodiversity, healthy soil, and habitat continuity.

-

Timber yield: Supporting economic viability through managed forestry.

-

Recreation: Facilitating human access through trails, signage, and safe environments.

-

Education and heritage: Preserving natural heritage and creating spaces for learning and reflection.

An effectively designed forest landscape should achieve all of the above, allowing each purpose to complement the others.

For example, wide trail corridors can double as firebreaks. Scenic clearings can be designed in areas where diseased trees have been removed. Boardwalks can protect sensitive wetlands while enhancing visitor experience.

Practical Techniques for Forest Landscaping

For students and practitioners alike, understanding the technical side of forest landscaping is essential. Below are some common methods used in creating visually and ecologically rich forest environments:

1. Selective Thinning

Removing weaker or poorly formed trees to enhance light, space, and health of the remaining stand. Also creates better sightlines and spatial diversity.

2. Understory Management

Clearing or planting shrubs and groundcover to add texture and control movement. For example, low-lying shrubs can prevent off-trail wandering and encourage pathway use.

3. Canopy Sculpting

Pruning lower limbs or shaping tree crowns to achieve light penetration, aesthetic profiles, or visual emphasis.

4. Strategic Planting

Introducing new species or replacing lost trees in key visual areas. Group planting or layered planting can mimic natural systems while offering aesthetic order.

5. Use of Clearings

Designing open spaces within forests for seating, gatherings, play, or scenic appreciation. Can also be used to restore meadow ecosystems or promote biodiversity.

6. Pathway Design

Curved vs straight routes, width, surface materials, and wayfinding techniques all contribute to how people interact with and perceive the forest.

Educational Takeaway: Learning to “Read” a Forest

For students of landscape architecture and forest ecology, it’s important not only to learn how to design a forest but also how to “read” one. This means observing:

-

The succession stage of vegetation (early, mid, mature)

-

Tree species, spacing, and health

-

Natural patterns of light and shadow

-

Signs of wildlife presence and biodiversity

-

Evidence of human use and wear

Being attuned to these subtle cues helps inform design decisions that are sensitive, functional, and ecologically grounded.

Real-World Applications and Career Opportunities

The principles of forest landscaping are increasingly relevant in:

-

Urban forestry: Integrating wooded elements into city parks, greenways, and ecological corridors.

-

Wildlife reserves: Designing trails and viewing areas that balance human use with habitat protection.

-

Resort and tourism planning: Creating immersive forest experiences that support eco-tourism.

-

Post-disaster landscape restoration: Rehabilitating burned or storm-damaged forests with new design-led planting strategies.

As climate change reshapes ecosystems, forest landscape design becomes essential not only for beauty — but for resilience, public health, and climate adaptation.

Final Thoughts: Designing with Nature, Not Against It

Forest landscaping is not about imposing order on wild nature — it’s about revealing the inherent beauty and function already within. By collaborating across disciplines, using ecological wisdom, and designing for both present and future needs, we can create forests that are restorative, sustainable, and deeply inspiring.

For students, this is a call to study both design and ecology. For professionals, it is a reminder to look beyond timber and trails, to the emotional and visual potential of every tree and trail bend.

After all, when a forest is thoughtfully designed, it doesn’t just grow — it lives in the minds and memories of all who pass through it.

Landscaping has been a known for making a certain place look good. Also it has been applied in forest and has been giving forests clean and would be more useful. With the easy guide and steps it has been made easy for us to follow.

Forest landscaping is something that I have always wanted to do but the opportunity never came up.

Your right that forests that are not in their natural state can be very boring if you hike through them for hours and can be easily improved with a bit of forrest landscaping.

Jack