Architectural concepts are the foundation of every great design, guiding decisions related to form, function, materiality, and experience. The best architectural works are not just aesthetic compositions but are deeply rooted in conceptual frameworks that respond to site conditions, narratives, and structural innovations.

By analyzing the works of renowned architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Frank Gehry, we can better understand how concepts translate into real-world projects. This article explores different conceptual approaches—site-driven, narrative-driven, and structural concepts—and examines historical and contemporary lessons in architectural design.

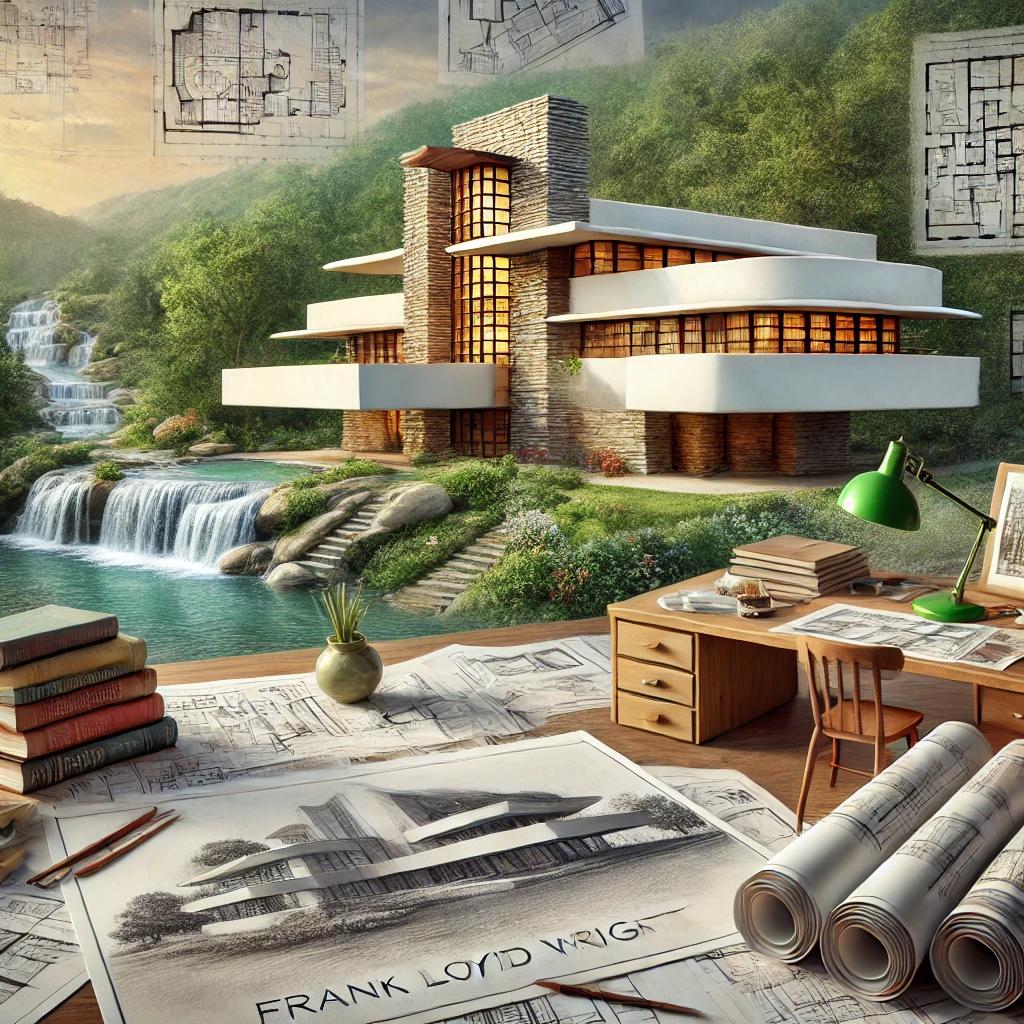

Frank Lloyd Wright: The Master of Site-Driven Concepts

The Philosophy of Organic Architecture

Frank Lloyd Wright pioneered the concept of organic architecture, a philosophy that sought harmony between human habitation and the natural world. His site-driven approach emphasized that architecture should emerge naturally from its surroundings, integrating materials, form, and spatial organization with the landscape.

Case Study: Fallingwater (1935)

One of the most celebrated examples of site-driven architecture is Fallingwater, designed for the Kaufmann family in Pennsylvania. Wright’s concept was to merge the home with the waterfall rather than merely offering a view of it. Several key principles defined his approach:

- Integration with Nature: The house is built directly over the waterfall, with cantilevered terraces extending over the rushing stream. This approach reinforces the connection between architecture and the natural landscape.

- Material Selection: Wright used locally sourced stone and concrete to mirror the rock formations found on the site.

- Open Plan & Spatial Flow: He designed spaces that extend outward, allowing interior and exterior elements to blend seamlessly.

- Low Profile & Organic Form: Instead of dominating the landscape, the home becomes part of it, emphasizing horizontal lines that mimic the surrounding topography.