As cities grow denser and urban life becomes more disconnected from the natural world, architects are turning to innovative solutions to bridge this gap. Enter biophilic design, a transformative approach that integrates nature into the built environment to enhance human well-being, sustainability, and aesthetic appeal. In 2025, biophilic design is not just a trend—it’s a movement reshaping how we conceive spaces, from homes to offices to public plazas. For architecture students, understanding biophilic design is essential to creating buildings that respond to modern challenges like mental health, climate change, and urbanization. This article explores the principles of biophilic design, its evidence-based benefits, and why it’s a cornerstone of contemporary architecture. By the end, you’ll be inspired to observe and incorporate biophilic elements in your own projects.

What is Biophilic Design?

Biophilic design draws from the concept of biophilia, a term popularized by biologist E.O. Wilson, which describes humanity’s innate affinity for nature. In architecture, biophilic design translates this affinity into intentional strategies that bring natural elements into buildings and urban spaces. It’s not just about adding a few potted plants; it’s about creating environments that mimic natural systems, engage the senses, and foster a deep connection to the outdoors.

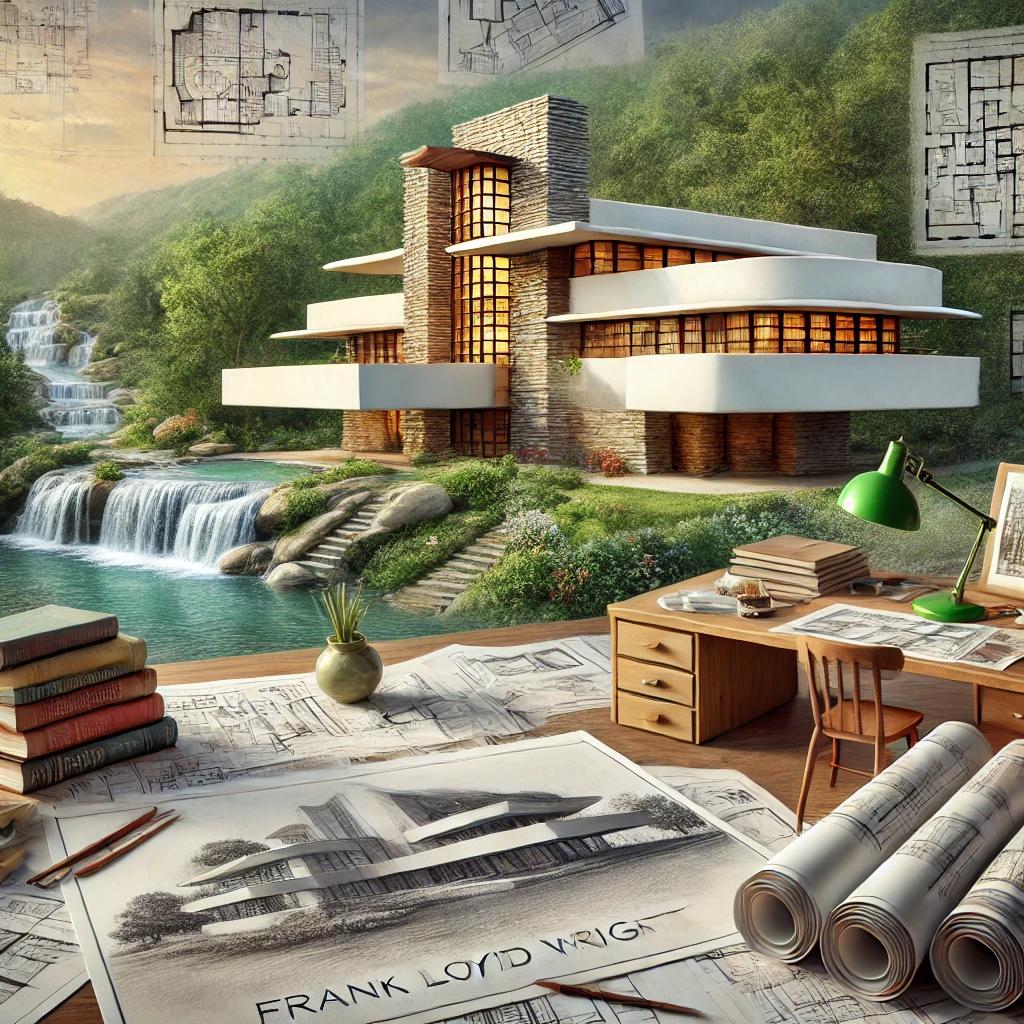

Unlike traditional architecture, which often prioritizes functionality and aesthetics over human experience, biophilic design places well-being at its core. It uses elements like natural light, greenery, water features, and organic materials to create spaces that feel alive and restorative. From towering green skyscrapers like Milan’s Bosco Verticale to cozy homes with expansive windows, biophilic design is versatile, applicable to projects of any scale or budget.

In 2025, biophilic design is gaining momentum due to its alignment with global priorities: sustainability, mental health awareness, and resilient urban planning. As architecture students, you’re at the forefront of this shift, equipped to shape a future where buildings don’t just shelter us—they nurture us.

The Principles of Biophilic Design

Biophilic design is grounded in a framework of principles, most notably the 14 patterns outlined by environmental psychologist Stephen Kellert and colleagues. These patterns provide a roadmap for architects to integrate nature meaningfully. Below, we explore the key categories and examples of how they manifest in architecture.

1. Direct Experience of Nature

This category emphasizes tangible connections to natural elements. It includes:

-

Visual Connection with Nature: Designing spaces with views of greenery, such as gardens or forests. For example, large windows in a home overlooking a park create a calming effect.

-

Non-Visual Connection with Nature: Incorporating sounds, smells, or textures, like the sound of a water fountain or the scent of cedarwood.

-

Presence of Water: Using water features, such as indoor streams or reflecting pools, to evoke tranquility.

-

Dynamic and Diffuse Light: Mimicking natural light patterns, like skylights that shift with the sun’s movement.

A project like the Jewel Changi Airport in Singapore exemplifies this, with its indoor rainforest and cascading waterfall, immersing visitors in nature within a bustling urban hub.